Written under the supervision of doc. Clare Wallace, PhD, M.A., and submitted on 6 June 2011, this essay was part of my total coursework at the Department of Anglophone Literatures and Cultures at Charles University’s Faculty of Arts. The essay is published with the kind permission of the faculty.

Aspects of the Pygmalion Myth Transformed in The Shape of Things by Neil LaBute

Introducing Pygmalion, Bernard Shaw made use of the juxtaposition of two conflicting beliefs. One the one hand, his opinion that it is in the capacity of all human beings to completely refashion themselves, and on the other his conviction that persons so transformed were always themselves even before the metamorphosis (Shaw, XIV). Apart from being a delightful comedy dealing with the motif of transformation, Pygmalion presented its viewers with a message of social criticism, pointing out the folly of strict and unsurpassable social division, and stressing the merits of general human equality. Not even a hundred years went by when Neil LaBute offered a brand new take on the notorious story of Pygmalion. In spite of having a lot in common with the 1912 piece of drama, LaBute’s the shape of things was bound to alter not only many a minor detail but also some basic elements of the plot in order to make the story more appealing and plausible to the modern viewers. This essay discusses the ways Neil LaBute transformed and updated G. B. Shaw’s Pygmalion in his play called the shape of things.

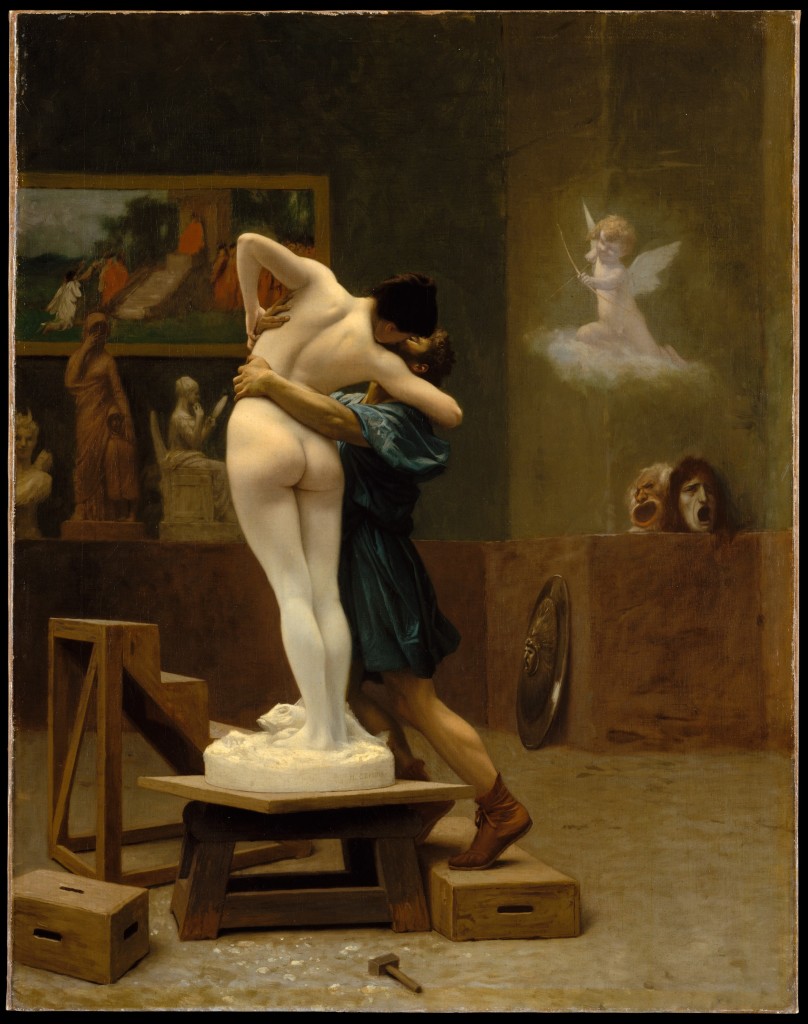

„Pygmalion and Galatea,“ painting by Jean-Léon Gérôme, photo in public domain, accessed via The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The most prominent alteration is the obvious gender shift in the characters of the executor and the subject of the transformation. While Shaw has a male character helping a damsel in distress, so to speak, to appear more socially agreeable in order to be able to run her own flower shop, LaBute goes in the opposite direction and has the instigator of the change be a woman which opens a question of our understanding of gender roles in the society. In the beginning of the twentieth century, before the rise of feminism and the sense of female independence, it must have been only logical that the helpless person in need of aid was a woman, and while it would certainly not appear unfit today, having the roles reversed is in its essence much more interesting, even provocative. After all, it is an established social paradigm that men do not need to be helped, let alone by a woman, and in regard to their appearance. LaBute thus asks the audiences what is acceptable for a man to do, and what would they already find unsuitable. Is it fit for a man to undergo a cosmetic surgery or not? LaBute is reluctant to give us a clear answer. Adam, despite his willingness to have his nose surgically corrected, eventually only feels ashamed and opposes admitting the fact to his friends. The reason is at hand – male cosmetic surgery is in the contemporary society perceived as a taboo. Our understanding of masculinity is, however, not the only social issue the shape of things deals with.

Neither Shaw nor LaBute are overly shy in their critique of our obsession with surface. In Pygmalion, it only takes a number of elocution lessons, washing, and a nice dress to “make a duchess of this draggletailed guttersnipe” (Shaw, 29). The problem is therefore not in who the person is inside but in the way they appear and talk. As Shaw illustrates, in the society “it is precisely these superficial details which tend to be endowed with most significance, and upon which acceptability and its criteria tend to depend” (Mugglestone, 378). In the shape of things it also takes only a handful of superficial alterations to transform Adam into a man much more readily a gladly accepted by the society. The main contrast between the two plays in this aspect is that the characters have different reasons for both metamorphoses. The issue that dominates Pygmalion is class consciousness which is most obviously mirrored precisely in the linguistic signals of social identity (Mugglestone, 374). Elizabeth Doolittle yearns for a change because, being a member of a low class, she is unable to do what she wants. Therefore, she needs to at least look like she is from a higher social sphere. This motivation, however, would have never worked in a contemporary play. While not denying that there still is a certain class division in our society, a character opting for a radical change of appearance only for the sake of overcoming class boundaries would not seem very plausible. LaBute therefore replaced social class for sexual attractiveness. Adam is willing to do everything in order to change his external appearance so that he would be more appealing to Evelyn, and thus becomes “a living, breathing example of our obsession with the surface of things, the shape of them” (LaBute, 121). Nevertheless, it would be wrong of us to assume that, in Pygmalion, Eliza endures the transformation merely for the sake of climbing up the social ladder. When showing her concern with her future marital prospects, Mr. Higgins comforts her by saying that “the streets will be strewn with the bodies of men shooting themselves for your sake before Ive done with you.” In spite of this, though, any concerns about sexual attractiveness are overshadowed by the aforementioned issue of class consciousness.

Another modification which the story of Pygmalion sustained in the shape of things is the primary driving force of all the main characters. Let us begin with the ones who undergo the transformation. Elizabeth demands to change herself out of her own accord. It is she herself who is “coming to have lessons” (Shaw, 26) because she perceives it as the only way to be able to acquire the flower shop. Even though her final transformation is much more radical than what she initially asked for, it is her who made an informed decision to put the metamorphosis in motion. As opposed to Shaw, LaBute is much more fascinated “by the sacrifices individuals are willing to make in return for very little, for momentary satisfactions” (Bigsby, 92). Adam goes through with every single alteration because he is manipulated by Evelyn into believing that he does so out of pure and requited love. Unlike Elizabeth, Adam is utterly blind and even though he may not think that, he is certainly not the one who has control over his decisions. Whereas the point of Pygmalion “is the independent autonomy which Eliza achieves, denying her status as Higgins’s mere artifact” (Shaw, XVIII) in the shape of things we, in a way, watch Adam become precisely such artifact. In consequence, LaBute’s play evokes in its audiences a feeling of compassion with him. As the author himself admitted, “it is more interesting to write about one or more people who are being awful to other people because it makes for exciting, dramatic fare” (Bigsby, 81).

Regarding the characters who are in charge of the transformations, their roles are in relation with the transformed ones completely reversed. While Higgins acts essentially out of affection and Pygmalion is thus “driven by a kind of love” (Bigsby, 87), Evelyn does so in order to get what she wants – to get enough data to successfully finish her thesis. It is true that Higgins agrees to work on Elizabeth mainly for his own amusement, as well as because of his bet with Pickering, but as he in the end admits to Elizabeth, he has “grown accustomed to your voice and appearance. I like them, rather” (Shaw, 101). In a direct opposition to him, Evelyn coldly concludes that she did not do anything “out of love or caring or concern” (LaBute, 120) but only to point out the shallowness of our society. Thus, she becomes a truly fiendish character and makes it easier for the audience to feel compassionate about Adam. In a way, it makes the play soothingly black and white.

With respect to the motivations of the main characters, we also have to mention a very powerful one – sex. It would be fruitless to attempt to look for any indications of a sexual relations between Elizabeth and Higgins for Shaw makes it very clear that their relationship, however affectionate in the end, is strictly platonic. Higgins is simply “not sexually attracted to Eliza” (Shaw, XVII). In an actual fact, he doesn’t even make any distinction between the sexes, treating everybody in the same unaffectionate manner, be it a man or a woman, a flower girl or a duchess. The situation with Evelyn, however, could not be any more different. It is through her seeming emotional and obvious physical love that she manipulates Adam. Since our society is indisputably more open to the allusion to sex on stage than the turn-of-the-century audiences, it is only justifiable for LaBute to use it. It makes Adam’s situation perhaps more relatable, the audiences more compassionate, and Evelyn definitely more wretched. Using sex as a tool elevates her foul manipulation to a whole new level and, once again, makes her the number one enemy in the play.

So far we have only discussed social issues and characters, but it is time now to focus our attention on the transformations themselves. We can only argue where our fascination with people changing either for better or for worse originates. Perhaps in the hope that it is not impossible for us ourselves to do the same, and the assurance that our situation is not nearly as bad as it could be. Be it as it may, it is a fact that we seem to be very interested, in some cases even obsessed, with the before-and-after images, with the evidence of the great metamorphosis. Exactly for this reason, we are given – by Shaw in Pygmalion in particular – specific details about Eliza’s appearance in order to have a concrete image in mind to which we may compare the final “creation”. It may only be perceived as a shortcoming of Pygmalion that we are not given much of a chance to see the actual metamorphosis of Elizabeth. Instead, we are essentially presented with only two scenes in which we can see her change. In the first one, she takes a bath and puts on a clean dress, and in the other one she learns to pronounce the alphabet correctly. LaBute, however, lets us in on almost every detail of Adam’s transformation. Not only do the characters frequently comment on his weight loss, healed fingertips, haircut, altered clothing style, and many other changes, we are even almost allowed to follow him to the doctor’s office where he is to discuss his cosmetic surgery. Precisely this attention to detail makes the gradual process all the more enjoyable. As the cliché says, it is the journey that matters, not the destination.

Both plays also differ in the degree of transformation the two characters undergo. Whereas it suffices Eliza to bathe, put on decent clothes, and learn to enunciate properly, the situation with Adam is much more complicated. His metamorphosis only begins with the different clothing style, follows with a substantial loss of weight, and peaks with a direct interference with his body in the form of a cosmetic surgery. LaBute thus lays an intriguing question before us: How far are we willing to go to change ourselves either for someone we love, or for ourselves.

Both Bernard Shaw and Neil LaBute are very similar in what they do in Pygmalion and the shape of things respectively. Employing a clever social critique they strive to make their audiences reflect on what they do, and whether it is right. Shaw claimed that in this play he wanted to “chasten morals with ridicule” (Crane, 879) and indeed he “satirizes the idea of human difference exemplified in the construction of class” (Shaw, XIV). LaBute took on his legacy and adapted his play, leaving only the basic skeleton and altering essentially everything else. By doing so, he made sure that even those members of the audience who are familiar with the original play and who correctly discover its thread in the story, end up surprised or even shocked when the play is over. All of his alterations also prevent the play from appearing obsolete, make it up-to-date and more plausible, and also make it easier for the audiences to empathize with the characters. However, it is also true that only a minority of people will put together all the similarities and discrepancies of both plays when they see it for the first time, but that is not really a problem. It only makes it easier for us to return to it again, look at it with a fresh pair of eyes, and enjoy the play even more than the first time.

Bibliography:

Bigsby, C. W. E. Neil LaBute: Stage and Cinema. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

Blake, Jason. “The Shape of Things.” The Sunday Morning Herald. 26 May, 2011. 26 May, 2011. < http://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/theatre/the-shape-of-things-20110323-1c6m5.html>

Crane, Milton. “Pygmalion: Bernard Shaw’s Dramatic Theory and Practice.“ PMLA December 1951: 879-885.

LaBute, Neil. the shape of things. London: Faber and Faber, 2000.

Mugglestone, Linda. „Shaw, Subjective Inequality, and the Social Meanings of Language in Pygmalion.“ The Review of English Studies August 1993: 373-385.

Shaw, Bernard. Pygmalion. London: Penguin Classics, 2003.

Napsat komentář